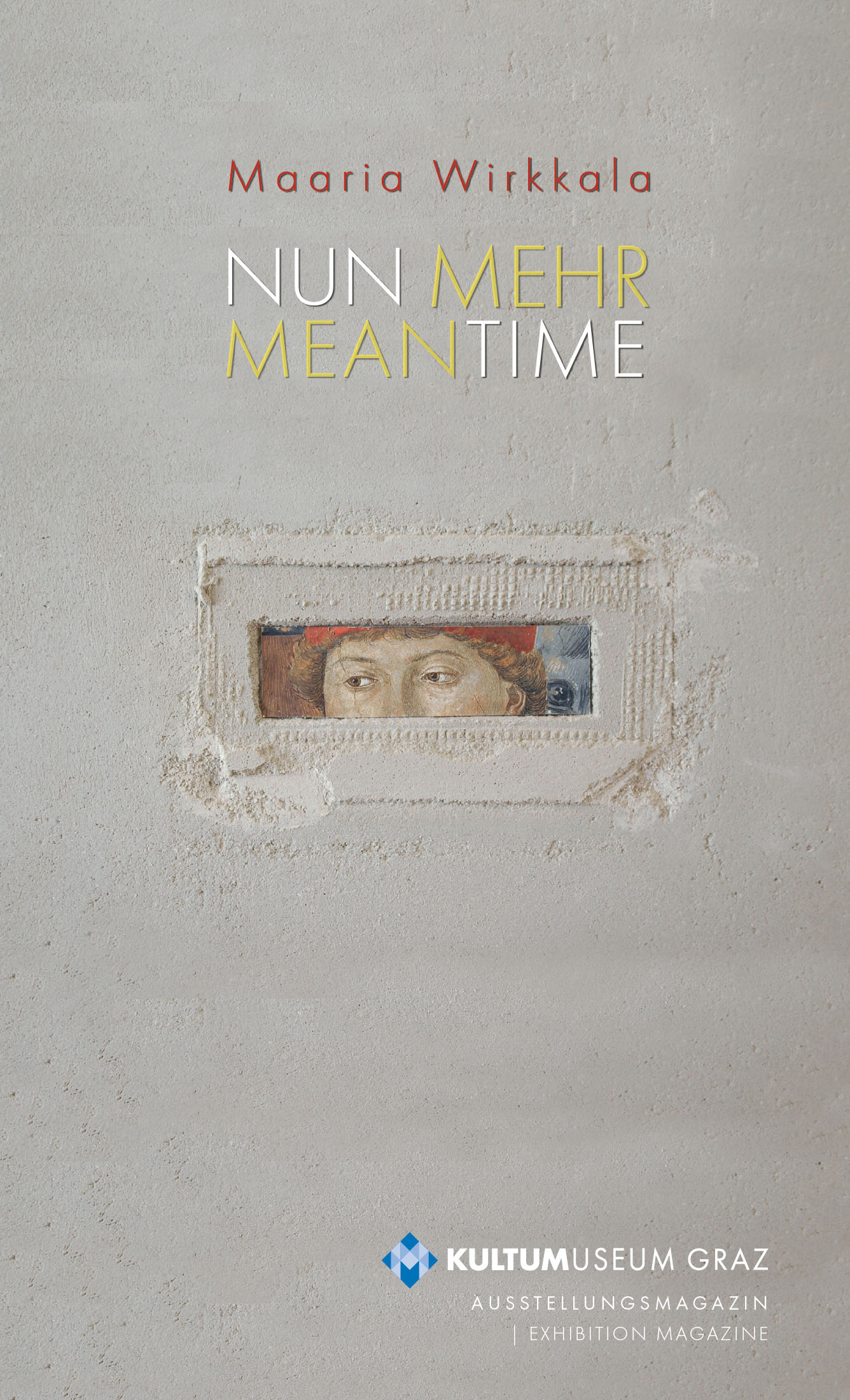

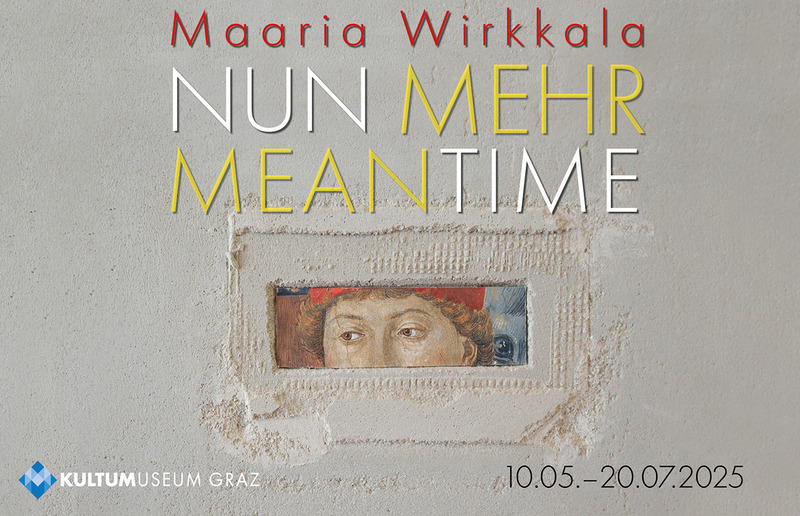

Maaria Wirkkala: NUN MEHR – MEANTIME

In 2011, a procession of animals walked across the courtyard of the Minorite monastery at dizzying heights, heading towards a place of longing inspired by a child‘s drawing of angels. The child in question was Maaria, who was four years old at the time. This place can now be found in the small tower chamber, from which split stones spill out. At the time, the balancing animals were a metaphor for refugees — four years before the so-called refugee crisis began to alter this continent‘s empathy. Where has this continent now tilted? Where has the entire globe gone? No one is spared the dizzying abyss now. Everything is different now.

However, the exhibition title draws attention to the blank space. It is not a insistent “NUN MEHR”, but rather a bold assertion: NUN MEHR! One might hear the German word for ‚sea‘ (Meer), as well as the insatiable German word for ‘more’ (mehr), which corresponds to magis in Latin.

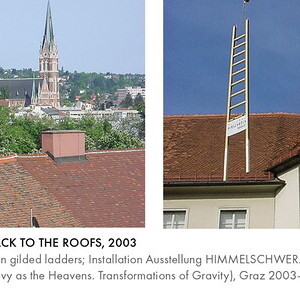

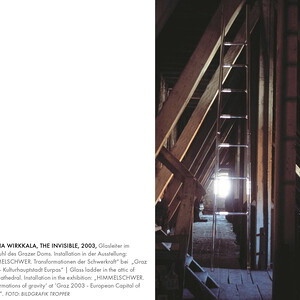

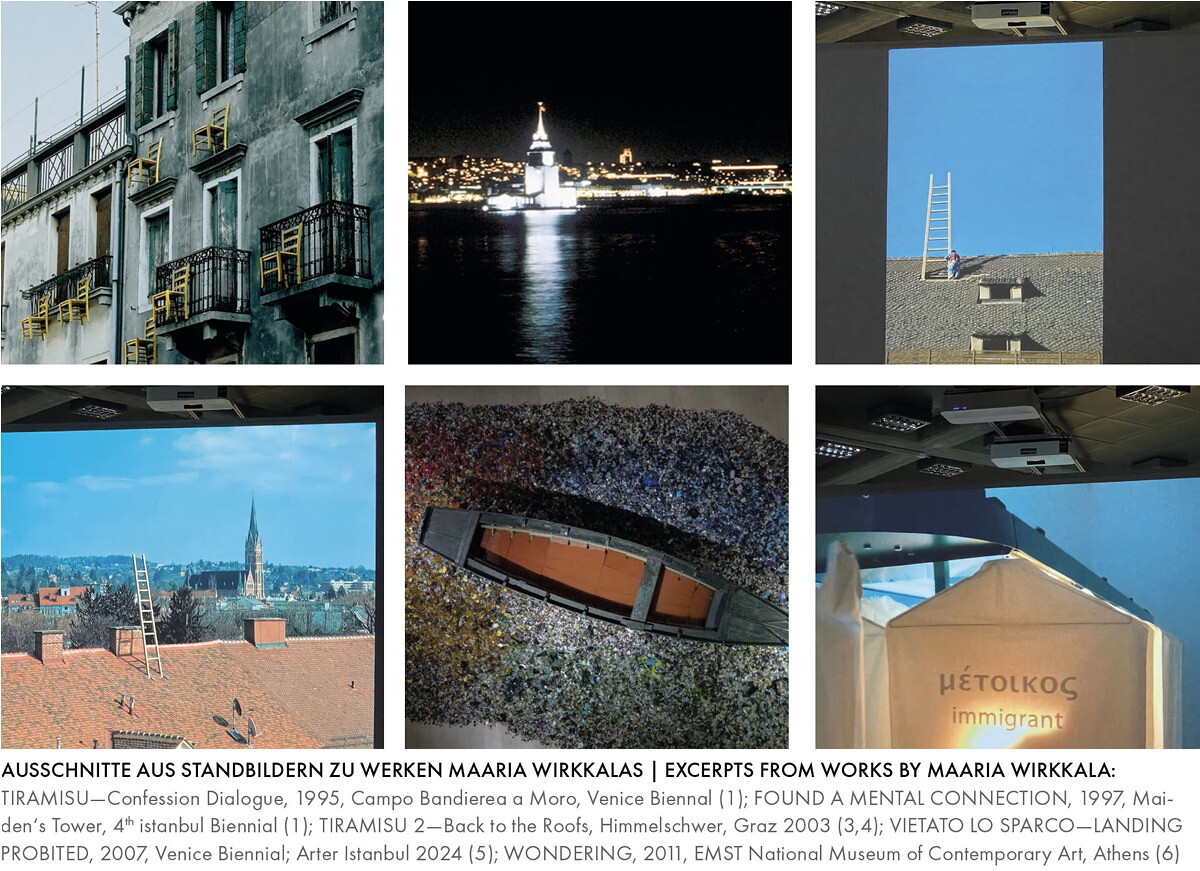

The beginning of the current exhibition is once again marked by the monastery courtyard, whose cloister from the early 17th century with its Tuscan columns was extensively renovated in 2020/21. But one thing was forgotten - until today: the first stage was still a temporary structure in the form of a building post until this exhibition. Maaria Wirkkala is now making a clear start for this museum, which is in a historical site and is searching for traces of religion in contemporary art: she proposed replacing the first step with a solid oak step and gilding the height to the tread. It was carried out by the same carpentry firm that put four twelve-meter-long ladders through the historic roofs of Graz‘s old town during “Graz 2003 – European Capital of Culture”. While it was vertical then, it is now the horizontal that is being refined by the artist, a supposedly small gesture. “ASPIRATION” is the title of this beginning, which, if you walk up the 400-year-old stairs, also fills the cracks in the first steps. They too are now gilded, as if a staircase that has gradually drifted apart over the centuries could be joined with gold. It is in the meantime. MEANTIME!

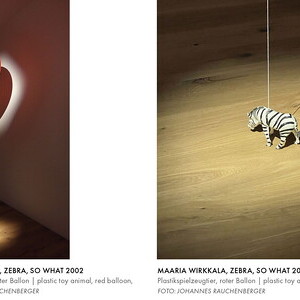

At the new entrance in the south wing of the exhibition, visitors are greeted by a red balloon delicately leading a small zebra on a ribbon. The scene opens with a cheeky question: “SO WHAT?“ Unbothered, the zebra continues to graze calmly, seemingly unaware of the oversized balloon hovering above. Nothing can happen to it. For the first time, a shadow of this image appears on the wall.

A few steps below, in the large exhibition space, four video windows reveal an old carriage floating in the air—like a carousel stretched across time. It returns again and again, reliably.

Its destination is its mission: “WAIT TO BE FETCHED.” The exhibition begins with a meditation on death: Barque, ladder, carriage—and the thought that someone is coming for us. Maaria Wirkkala restores meaning to these mythical images of transition, meanings long lost in the demythologizing gaze of modern worldviews.

The carriage moves in the opposite direction, above the treetops, ready to circle the soul when the body has become still and can no longer move. Maaria Wirkkala’s first video work was created in 2010 for a themed exhibition on death—“THERE IS A TIME FOR US ALL”—at the Lahti Historical Museum in Finland. The piece evokes the feel of shadow theater: a chariot drifts silently through the air. What children perceive as reality—what dreamlike images flicker behind the screen—is more than mere theater; for them, it is reality. At the edge of life, images of faith begin to appear. “WAIT TO BE FETCHED” is not a shadow play. The carriage truly travels above the treetops. Wirkkala is known for making the impossible possible—especially in her approach to death. The historic carriage, deemed “untouchable” by museum officials, was lifted into the sky by crane. “Waiting to be fetched” is a meditation on faith at the threshold—faith that reaches beyond the finite.

Each exhibition space reveals its own sensual and aesthetic characteristics. Before leaving the south wing on the second floor via the stairs, you will see two golden skis marking the slight incline directly above them.

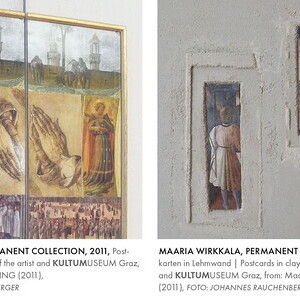

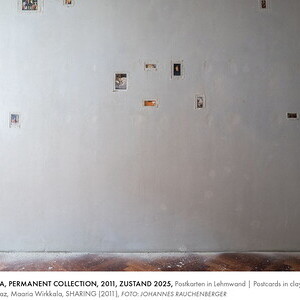

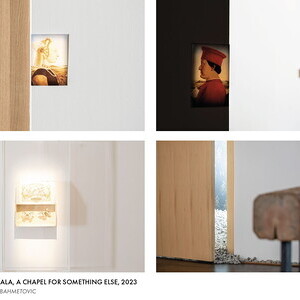

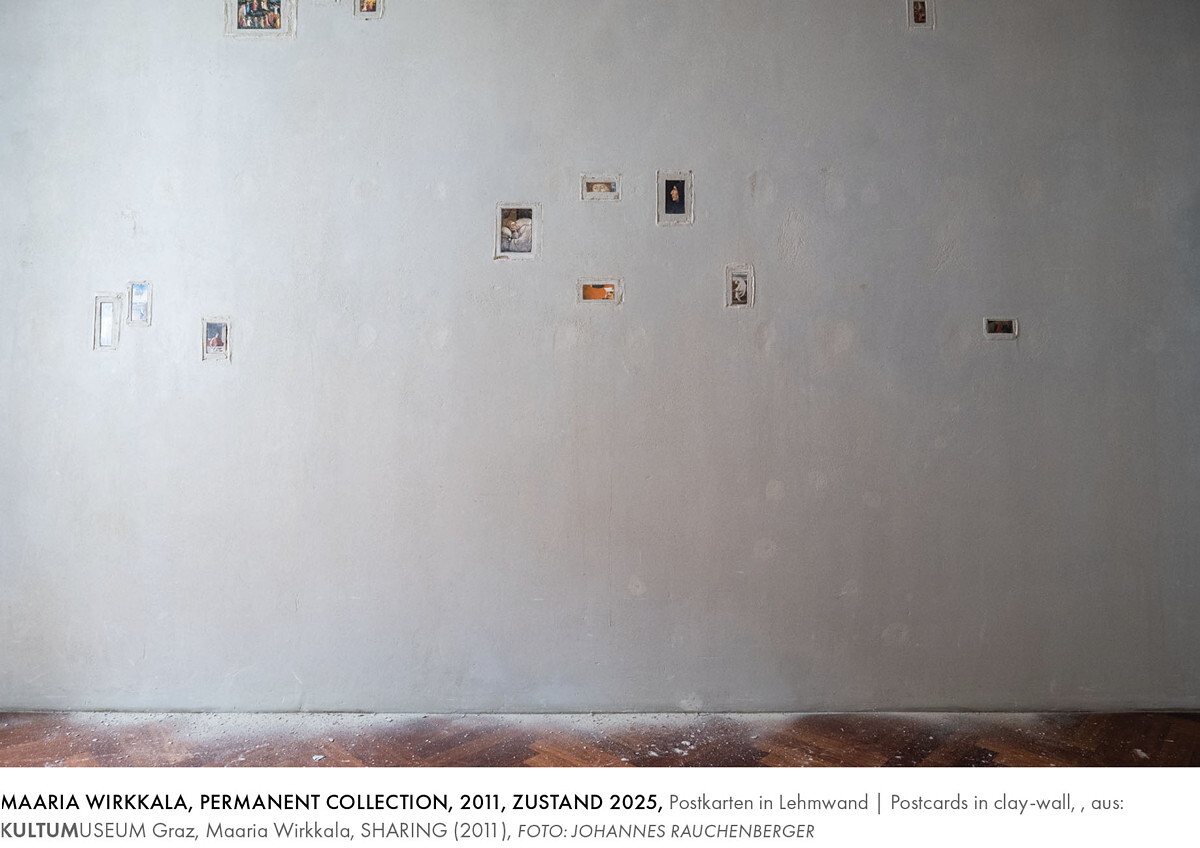

In the west wing, the exhibition unfolds with the rediscovery of Maaria Wirkkala’s artistic intervention from the 2011 show “SHARING”—the first solo exhibition held in the newly conceived and designed gallery spaces. Back then, she embedded early Renaissance paintings beneath layers of clay, creating a provocative gesture of concealment and revelation.

Now, in “NUN MEHR – MEANTIME” (2025), these clay coverings will be removed once again. In 2011, the Museum of Religion in Contemporary Art was still just a vision. Believing that such an institution deserved a “permanent collection,” Wirkkala donated one—surprisingly, not of contemporary works, but of masterpieces from the 16th century. Fra Angelico, Ghirlandaio, Gozzoli, Piero della Francesca, and even Hieronymus Bosch are among the names represented. Through stories of the Last Judgement, conception, pregnancy and encounter, violence and sharing; in the first experiments with perspective, in portraits, in the slumber of Saint Ursula, the gaze of Savonarola on a young man’s curls, in the dancing choirs of angels, the praying hands, and the battlefields of history—the rich tapestry of Western painting becomes visible. This is a heritage we all share: SHARING. Above all, these are stories from real life. And so, in a bold and literal gesture, Maaria Wirkkala scraped open the gallery’s clay-coated walls—and uncovered the paintings.

Now, in “NUN MEHR – MEANTIME” (2025), these clay coverings will be removed once again. In 2011, the Museum of Religion in Contemporary Art was still just a vision. Believing that such an institution deserved a “permanent collection,” Wirkkala donated one—surprisingly, not of contemporary works, but of masterpieces from the 16th century. Fra Angelico, Ghirlandaio, Gozzoli, Piero della Francesca, and even Hieronymus Bosch are among the names represented. Through stories of the Last Judgement, conception, pregnancy and encounter, violence and sharing; in the first experiments with perspective, in portraits, in the slumber of Saint Ursula, the gaze of Savonarola on a young man’s curls, in the dancing choirs of angels, the praying hands, and the battlefields of history—the rich tapestry of Western painting becomes visible. This is a heritage we all share: SHARING. Above all, these are stories from real life. And so, in a bold and literal gesture, Maaria Wirkkala scraped open the gallery’s clay-coated walls—and uncovered the paintings.

In her 2011 artist’s diary, Maaria Wirkkala wrote: “SHARING • the escape • the resources • seeing and be seen • the boundaries of infinity • the cultural heritage by postcards.” Postcards are a central element of Wirkkala’s visual language. They reappear at key points in the exhibition—after the staircase, and finally, in the cells.

Most depict early Renaissance paintings from Venice and Florence, yet as miniature images, they also carry the weight of a bygone era and Wirkkala’s own personal history. Her archive of postcards reaches back to her grandmother’s generation—a time when people first began to bring home fragments of the aura and power of these artworks in printed form. After each exhibition, Wirkkala returns to her postcards. She cuts them apart and reassembles them, creating new constellations of meaning from inherited images.

In 2011, she designed one of the newly renovated exhibition spaces by inserting pieces from her personal collection into the clay walls, framing them sculpturally with the wall material and finally making them disappear beneath the surface of the wall. Her cards became an integral part of this permanent collection and open up the moments of “SHARING” our cultural heritage. The bridge between the visible and hidden world also reflects the fusion of individual and collective history, inscribed in the postcards themselves and with them in the exhibition walls of this museum. And the motifs of the Renaissance painters reflect the challenges of the present with those of the past. Wirkkala uses aesthetics to set a counterpoint against hatred and division. There is room for the present in the beauty of her works.

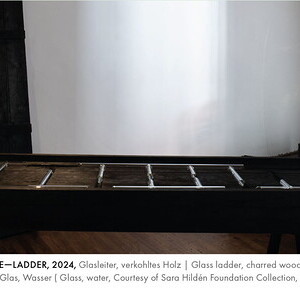

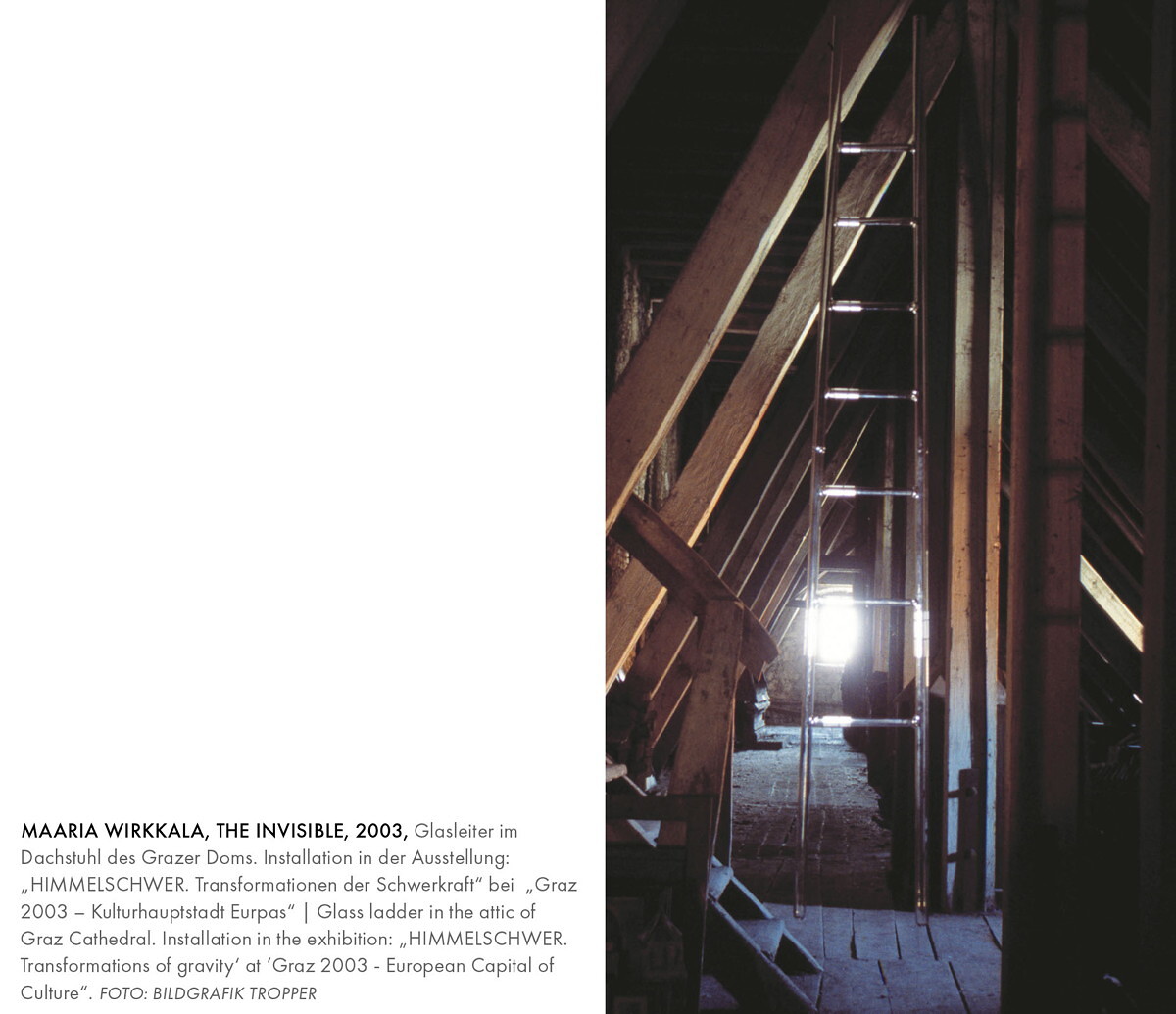

The next room presents, for the first time in this exhibition, one of Maaria Wirkkala’s most emblematic motifs: a ladder made of hand-blown glass. Suspended beneath the ceiling above a surface of red sand, it is titled “BEYOND THIS POINT”—a gesture toward the possibility of an imaginary ascent. This same ladder was first shown in the medieval roof truss of Graz Cathedral during the “Himmelschwer” exhibition at Graz 2003 – European Capital of Culture. Now, it defines the atmosphere of this space—an immaterial aid for climbing, weightless and intangible. To ascend a ladder made of glass requires more than physical effort; it must be entrusted to the soul or the spirit. Otherwise, the fragile structure would shatter under the weight of the body.

For nearly four decades, Maaria Wirkkala has embedded the poetry of ascent into the imaginary memory of spaces around the world. Through the delicate materiality of glass, she makes visible the invisible: the divide between above and below, between the finite and the infinite.

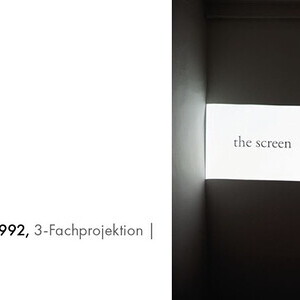

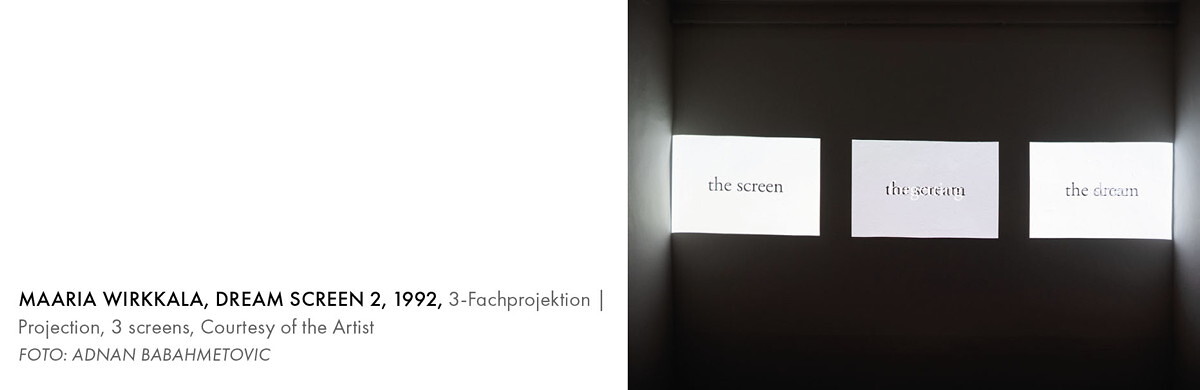

Maaria Wirkkala’s dreamlike visions do not shy away from the abysses and horrors of the world; quite the contrary, they often confront them head-on. Her seemingly abstract piece “DREAMSCREEN” (on display in the small room in front of Cubus), is an early video triptych from 1992 composed entirely of words. Projected onto three surfaces by a random generator, the words “the dream,” “the screen,” “the scream,” and “forgetting” appear in endlessly shifting combinations. In “DREAMSCREEN”, words stand in for dramatic images, representing both longing and the world’s horrors. Language itself becomes the medium for emotional and existential tension, suggesting that even abstraction can convey trauma, memory and hope.

At Cubus, visitors are invited to embark on Maaria Wirkkala‘s artistic journey spanning several decades, exploring the places she has transformed through her interventions. She has literally enchanted some of them. ‚Graz 2003‘ is also included, alongside Venice, Istanbul and Japan. She has opened the eyes of some places or given them new ones. MEANTIME!

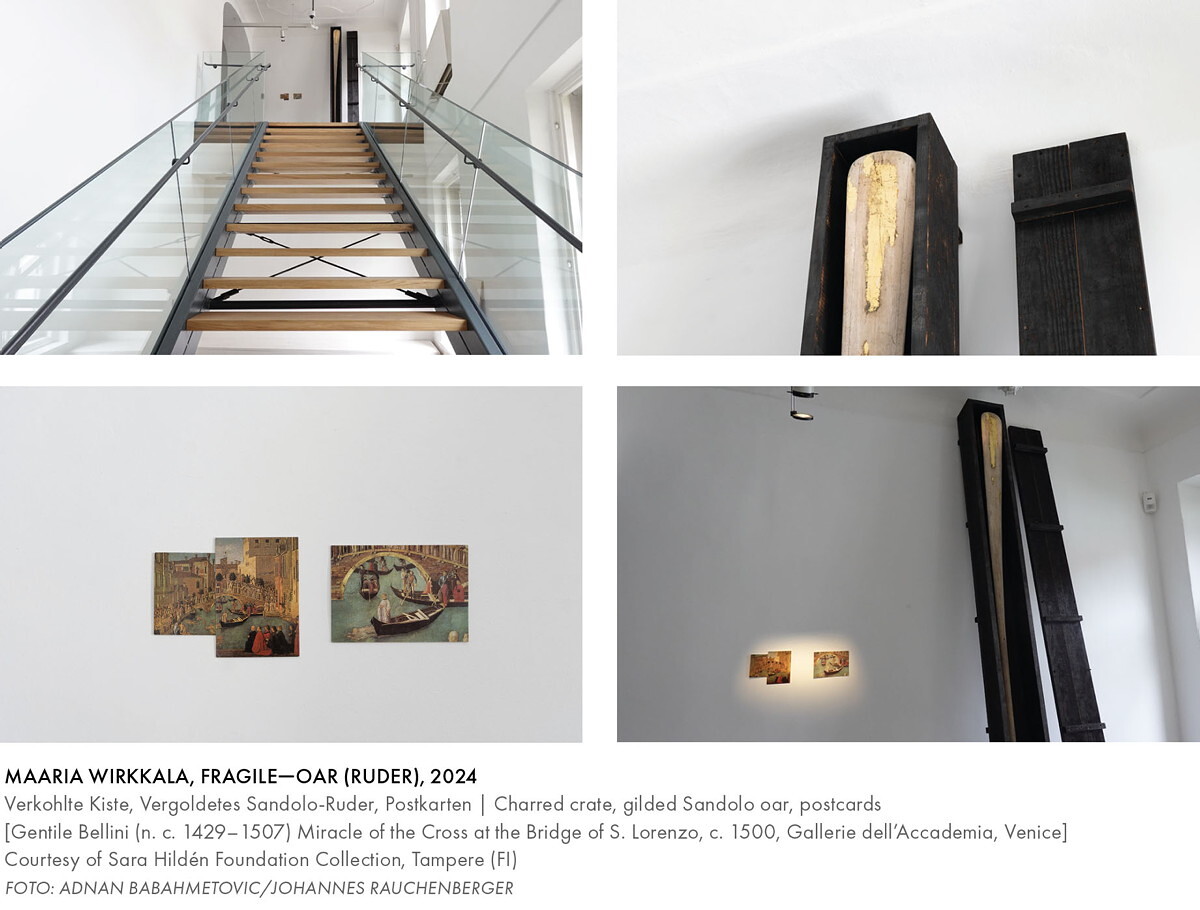

At the end of these steps, a first, room-high but very narrow, open box leans against the wall. Its surface is black; if you were to touch it, you would have ash on your fingers. It has been scorched and is charred. But inside is a treasure: an old Venetian oar with remnants of gold on it. Three postcards with different sections of one and the same painting by Bellini (the Miracle of the Cross) and the remains of the precious surface shift the tools for the water into the world of shipping in Venice. What can be discovered as a small detail on the map is here the precious interior.

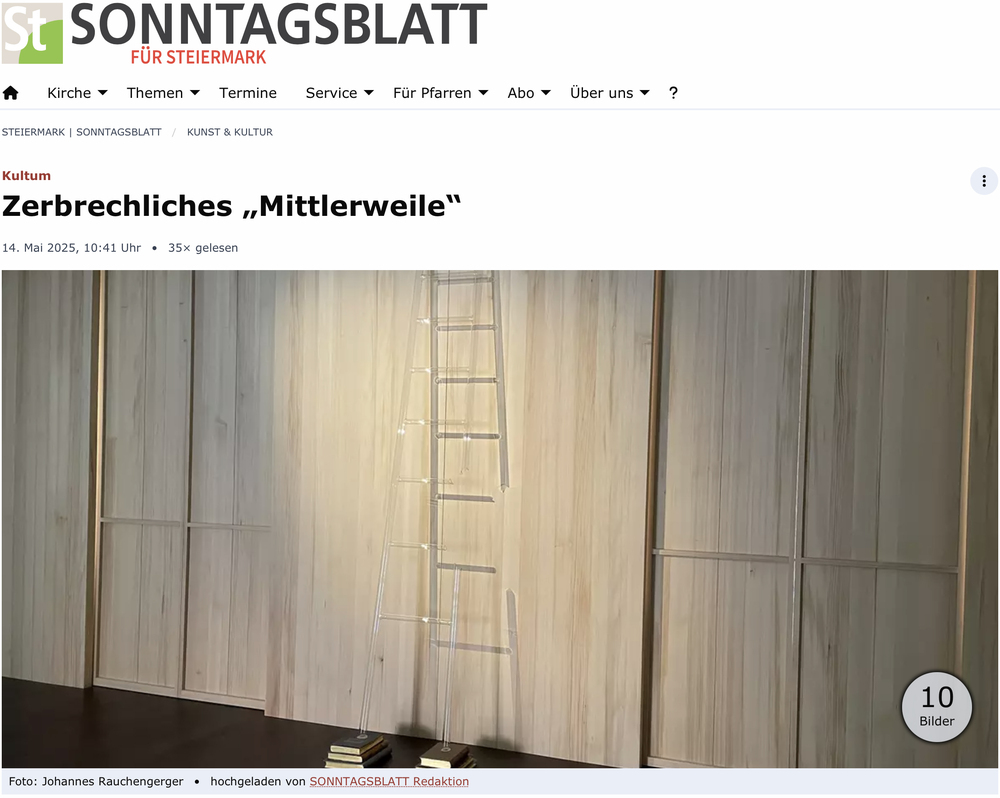

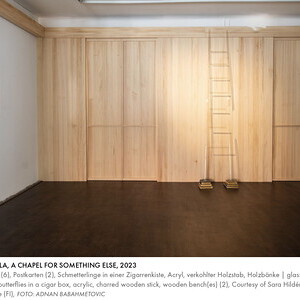

In the next room, Maaria Wirkkala has set up a “CHAPEL FOR SOMETHING ELSE”. Three gold-edged books form the basis of a floor-to-ceiling ladder from which a section has been removed. The ladder leans against the wooden wall. Where does it begin? Where does it end? Here, the shadow is more tangible than reality: precisely what has broken away from the ladder is clearly visible. The ladder is no longer simply a climbing aid; it is also a visualization of the invisible, shadow and possibility.

In the next room, Maaria Wirkkala has set up a “CHAPEL FOR SOMETHING ELSE”. Three gold-edged books form the basis of a floor-to-ceiling ladder from which a section has been removed. The ladder leans against the wooden wall. Where does it begin? Where does it end? Here, the shadow is more tangible than reality: precisely what has broken away from the ladder is clearly visible. The ladder is no longer simply a climbing aid; it is also a visualization of the invisible, shadow and possibility.

Maaria Wirkkala thus opens a further level of immateriality: the insubstantiality of the shadow enables the transparent glass to take on concrete form. This is one of the great themes of art and, above all, religion: Can the invisible be made visible? Maaria Wirkkala‘s art is about revealing and exploring the boundaries between the material and spiritual worlds. This ultimately creates movement in the sense of mental thought processes. However, it is not the ladder itself that guides the mental ascent, but rather the location to which meaning is ascribed. This also applies to the material from which it emerges or above which it hovers (like the floor below the Tennenrot sand from Fohnsdorf). Here, the basis is books with gilded edges. The titles remain hidden from view, but the image of a butterfly identifies them as science books. A second pictorial element is butterflies, prepared and displayed in a cigar box. A flamed wooden stick also leans against the wall. Two stools of different heights invite visitors to pause for a moment in this ‚chapel for something else‘.

Stones pour out of the door from the old tower in a direct reaction to the recent renovation of the exhibition rooms, which are bordered by pebbles. Inside is Maaria‘s childhood drawing of her ‚Enkeli‘ (angels), which is still reproduced as wallaper today. In 2011, the animals fled to it, which is a metaphor for refugees worldwide.

The echoing footsteps in the empty exhibition corridors direct visitors to the next place of contemplation in this old building.

In the axial space to the south wing, a room-sized photograph brings Istanbul into the exhibition rooms. Created 30 years ago, it is one of the oldest works in this show. “UNACCOMPANIED LUGGAGE” conveys both forlornness and dignity in an old, columned hall and the fear of bombs in pastries. It was recorded in the Yerebatan Cistern, an ancient water cistern in Istanbul. A gilded chair floats above the cistern water and its weightless shadow is cast on the old wall. A second image is also reflected in the water. A pair of red children‘s boots stand in the water and are also reflected, with their shadow visible on the wall. This large-format photograph extends the real space. The boots are also present in reality, standing on pebbles from which the large picture also seems to emerge. Why is there a fear of unattended luggage?

In the narrative of this exhibition, the artist‘s proposal is as follows: ‚FOUND A MENTAL CONNECTION‘. This title will appear three times, which is unique in Wirkkala‘s body of work. Naturally, its execution will be completely different. The first version can be seen in this exhibition: It is a sketch for the 5th Istanbul Biennial, which took place in 1997, and consists of small photo boxes. The title can be seen as a shadow in the final box. At the time, the well-known tower (Maiden‘s Tower/Kız Kulesi) on the Bosporus—a symbol of the border between the Orient and the Occident—could not be visited, but it is illuminated by glistening light and moonlight! – of gravity. „Forget the art, think of the fishermen!“ she realized during the dramatic process: she wanted the fishermen to remember her transformed tower. They did it.

Four years later, in 2001, Maaria Wirkkala‘s “FOUND A MENTAL CONNECTION II” was included in Harald Szeemann‘s Venice Biennale exhibition, On the Plateau of Humanity. It was there that Johannes Rauchenberger first encountered Wirkkala‘s work: a crowd of animals on a suspension bridge flowing towards each other from two bridgeheads. The bridgeheads formed of the Bible on one side and the Koran on the other. The work was also exhibited twice at KULTUM, in 2011 and 2017.

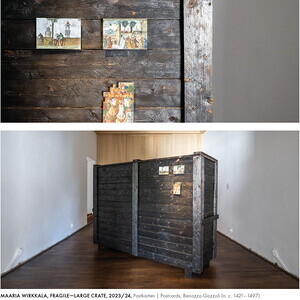

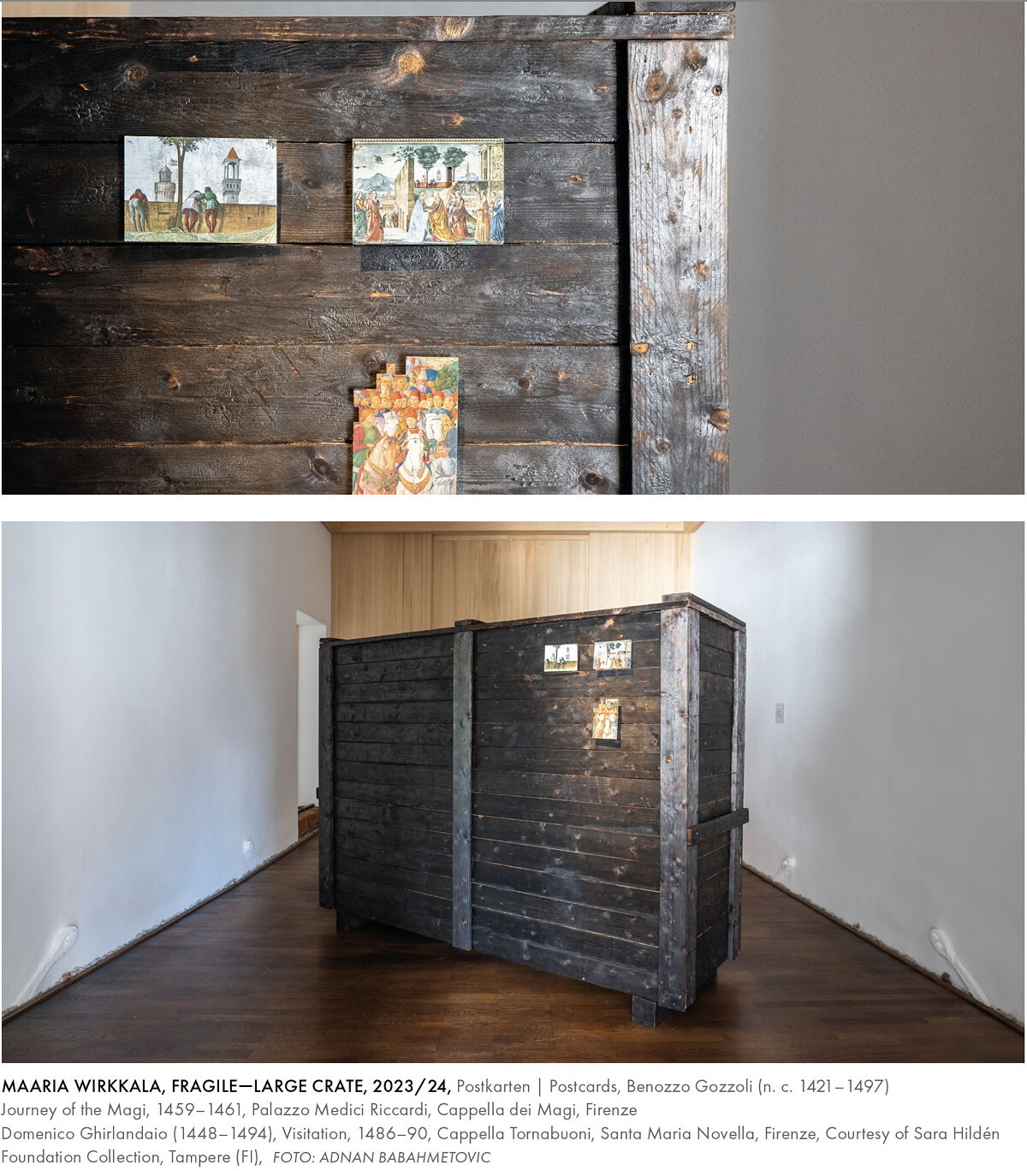

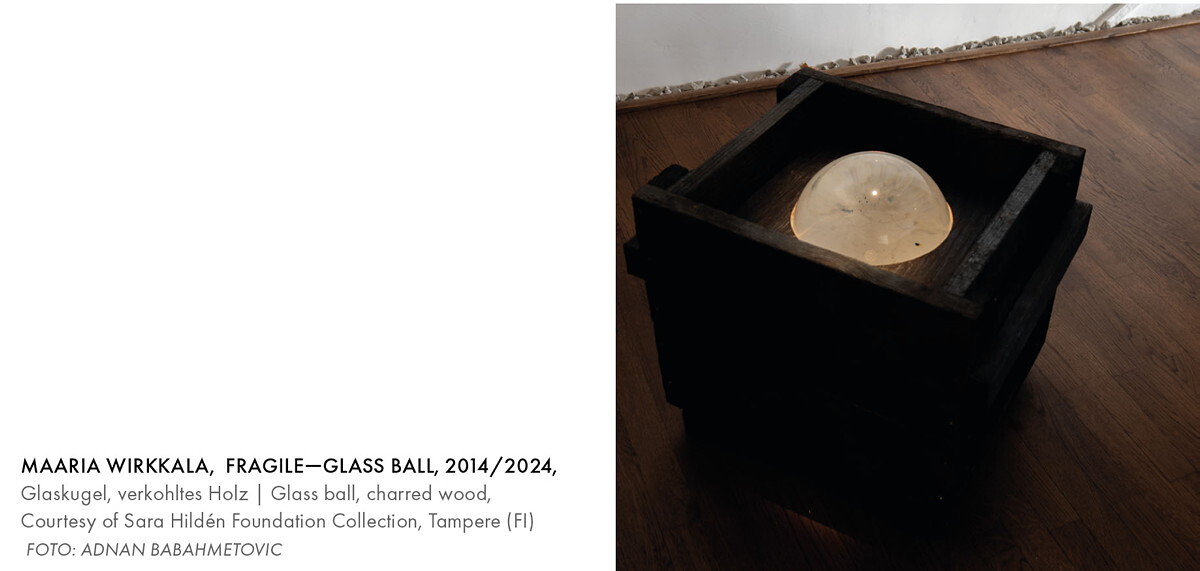

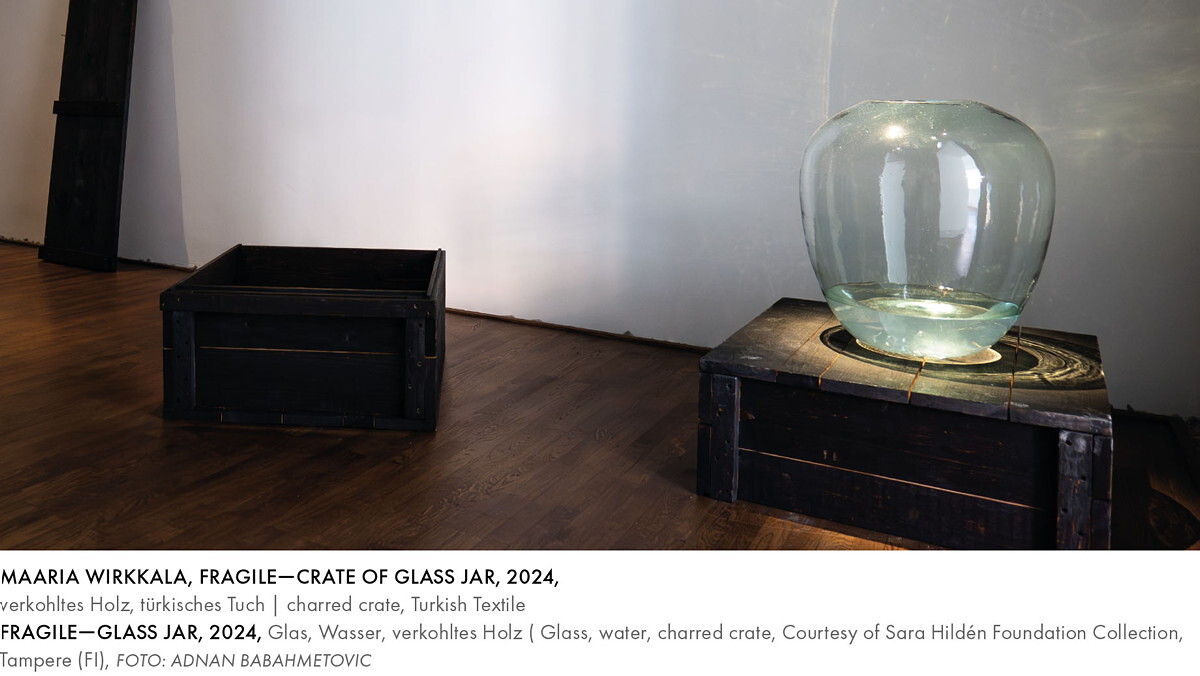

In this exhibition, the three interconnected cells of the historic monastery ultimately become a very special form of art ‚depot‘. Their entrances are marked with a transport label: ‚Fragile.‘ ‚When we try to overcome life‘s challenges or achieve something, we may find ourselves confronted with our own imperfections and vulnerabilities,‘ says Maaria Wirkkala of these works in a TV-interview.

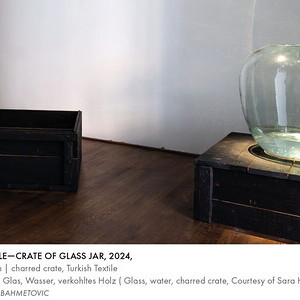

The boxes, which have shimmering black surfaces that feel sooty to the touch because they have been flamed, hold something inside. Most of them have covers, but they are leaning against the wall, exposing their contents. Everything in them is fragile.

The boxes, which have shimmering black surfaces that feel sooty to the touch because they have been flamed, hold something inside. Most of them have covers, but they are leaning against the wall, exposing their contents. Everything in them is fragile.

‚FRAGILE‘ is the description of all these objects: a golden chair, a golden ring, a glass ball, a precious vessel into which water drips from the ceiling and a glass ladder from which pieces have broken off. And a red piece of fabric from Istanbul.

However, the first large ‚storage box‘ is designed so that a person can fit inside it. Is someone in it? What or who is transported in such boxes? Once again, two postcards of Renaissance paintings are attached to the outside of the box, gleaming in the daylight coming in from the corridor. The postcards form part of Maaria Wirkkala‘s visual vocabulary, ‚[...] to define spaces‘. When the objects and elements are installed in different places, their character changes depending on where and how they are set up. This potential itinerancy of her works is precisely revealed in the boxes, as is the threat to the precious interior of the wrapping.

Maaria Wirkkala has ‚cropped‘ the cards, as can be seen in the ‚PERMANENT COLLECTION‘ on the floor below. She is particularly interested in the details. Take, for example, the inconspicuous wall above the main protagonists: the Virgin Mary and her cousin Elizabeth, who meet while pregnant in Domenico Ghirlandaio‘s (1448–1494) “Visitation” (1486–1490) from the Cappella Tornabuoni in Santa Maria Novella, Florence. However, in front of this wall, which the artist has cut out and reinserted behind her, three young men can be seen looking down from behind the wall. The contents of the large box and what is behind the wall remain hidden from us viewers. Benozzo Gozzoli‘s (1421–1497) “Journey of the Magi” (1459–1461) from the Cappella dei Magi in Florence (Palazzo Medici Riccardi) has also been cropped by the artist at the edge.

It is a matter of balance here, too. Of proportion. Of past and present. Finally, at the end of the corridor, there is a piece of work labelled “PROPORTIO”. A precious, hand-blown glass goblet by her father, the famous Designer Tapio Wirkkala, is suspended from the end of the corridor. The view extends beyond the beauty of the Minoritensaal façade to the garden.

However, the final room of the exhibition contradicts the beauty that fills these spaces. Menacing glass syringes, painful to look at, are aimed at the viewer (there is a hospital directly behind them). The syringes appear to float in the glass wall. Are they intended to alleviate pain? Or do they lead to delirium? Are they aids to drug intoxication? Whatever. In any case, the title is a question: “ENOUGH?”

POSTSRIPTUM: Once again an opening is covered, but this time it is not a window with syringes, but an entire door that prevents entry into the cell behind it: glistening light streams from its joints.

Johannes Rauchenberger

Maaria Wirkkala, born in 1954, lives in Espoo (Finland) and in the south of France. She has enchanted many places around the world. Some of them can be seen in a slide show at Cubus. She almost always works site specific with the material she finds. She has taken part in the Venice Biennale three times, once representing Finland. She has worked with the curators e.g. Harald Szeemann and Renè Block, who also opened the last retrospective at the Sara Hildén Art Museum in Tampere (Finland), which Sarianne Soikkonen curated. The works in the show in Graz come from the Sara Hildén Art Museum and the artist, for whose loans we are greatly indebted.